OPINION: Why read Edmund Burke today?

We’re looking to be inspired from writers and thinkers that we know, and get more people thinking (it’s one of the first Steps in our ‘Steps to Togetherness’ project!), and see what these writers, academics and politicians can bring to the ‘food for thought’ table – as we consider the role of civil society and our growing ‘community of community leaders’ network in their collective endeavours helping to hold communities and our wider society together.

Frances Ward is a theologian and writer. She served as the Dean of St Edmundsbury Cathedral in Suffolk from 2010 to 2017, and recently as an Anglican priest in Workington, Cumbria.

Frances Ward

One of our founder directors, Mark Ereria-Guyer took himself off to meet long-term friend and fellow ‘bookclubber’ Frances Ward. She has admired the thinking of Edmund Burke, an 18th century English philosopher, for many years and has recently completed her PhD in Durham University on his writings with a book due for publication.

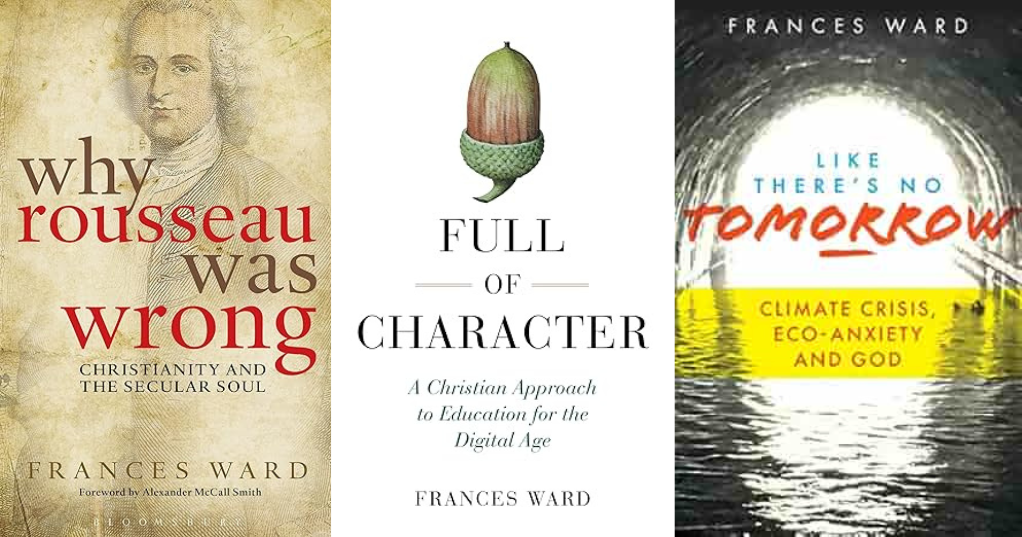

Frances is a prolific writer having published several books, including Why Rousseau was Wrong (Bloomsbury, 2013); Full of Character (Jessica Kingsley, 2019); Like There’s No Tomorrow (Sacristy, 2020).

Mark: We work with diverse communities across the UK and I am not sure many of them will have heard of Edmund Burke, why do you think we should dust down his books and ideas some 200 years later?

Frances: Yes, I am often asked that! One good reason is that he took issue with that other major English philosopher Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes argued that the natural state of humanity was ‘war of all against all’ – and it doesn’t take much to see how prevalent that view is today.

We are led to understand ourselves as atomistic individuals, with autonomy, power and rights, asserting ourselves and our ‘identities’ competitively in a world where we create our own meaning over a nihilistic void. In his 1651 book Leviathan, Hobbes contended that those warring individuals could only be held together by contracting into society that found its unity in an absolute ruler, who provided security over against the abyss that lay beyond the boundaries of society, and over against other separate nation states. So, like autonomous sovereign individuals, the state was naturally at war with all other states, unless they could develop treaties to establish an uneasy peace. Sovereign individuals, sovereign states.

Mark: So this is why we need civil society to hold us all together and overcome the temptation towards the worshiping of, all too familiar, hero-style leadership we see across the world?

Frances: In many ways this is so. Burke looked back to older traditions of thought to commend a very different way of being a human being, and of living together in society, locally, regionally, nationally, internationally.

I see his contribution to political thought as having four aspects.

Edmund Burke (portrait by Joshua Reynolds c.1769)

First of all, ‘power’. Burke didn’t believe that human beings are naturally competitive, divisive and motivated to possess power. For him, power was not an individual possession which you either have, or don’t have, but something everyone has in different ways. All human persons hold power, as stewards, to serve the purposes of love, in public service to build the common good for all in society, especially the weak and vulnerable. We should judge ourselves and others on how we use power in public service of others. The call of duty, as Burke astutely knew, is always a limiting of power: ‘I am well aware, that men love to hear of their power, but have an extreme disrelish to be told of their duty. This is of course; because every duty is a limitation of some power,’ he commented.

Second, Burke had an imagination for the ‘whole’, not the ‘part’. He did not understand human beings to be atomistic individuals, but parts in a greater whole. He looked back to St Paul, who in his first letter to the Corinthians (chapter 12) commended that all people belong to the one body – each with their different gifts, and each indispensable.

So instead of Hobbes’s world of nihilistic chaos in which humanity constructs society as an uneasy body, yoked by violence and fear together, Burke saw the body politic of co-operation, incorporation, where all are valued. Here’s an example. A Hobbesian imagination operates on the roads. It’s a belonging of fear – that we might hit the other car, or some object, or person, and cause costly damage – that’s why the community of the road works – held together in mutual tension.

Contrast that with an orchestra, where each member contributes different skills and instrumental sounds to create a work that is more than the sum of its parts – a piece of music that transcends its makers, but which needs the individuality of each member, for it will be diminished if the flautist, or cellist, or timpanist, is missing. An orchestra is held together not by mutual tension, but by common purpose and love of their endeavour.

Burke’s sense of the body politic looked back to Cicero and Aristotle, to St Paul, via Hooker, Aquinas and Augustine, to the one body of Christ, in whom there was neither Jew nor Greek, male nor female, free nor slave, as each member transcends their own identity, inspired to belong within a whole body, participating with a sense of empathy and delight in diversity, held together in love.

So not the love of power, but the power of love, and an imagination for the ‘whole’ rather than the individual ‘part’.

Mark: That dynamic sense of shared identities, and being inspired by a sense of empathy and ‘delight in diversity’ is so core to our National Lottery funded project: 32 Steps to Togetherness. It is a set of actions and behaviours that can be nourished and treasured, by as you say ‘the power of love’! In the UK today, and across much of the world, to use your analogy, all the members of the orchestra are somewhat childishly stamping on their own instruments, throwing away the musical score that holds everything together?

Frances: Absolutely, and that brings me to the third aspect that Burke contributes to political thinking. Edmund Burke was perhaps the first to identify the power of utopian ideology to capture the imagination of societies and peoples. He thought the associations, institutions and constitutions that we are born into – and the family is the first place we belong – require reform, of course, and should always be alive with self-critique. But he absolutely refuted that ditching everything for the sake of some blueprint, or utopian dream, was a good thing to do.

In fact, that’s why he hated the French Revolution so much: it overturned all aspects of society – and the end result of that was the emergence of autocracy: the tyrant, Napoleon. Autocrats will always say they will bring in the revolutionary new, and they do this by destroying constitutions and institutions, especially by politicising the judiciary and overturning, or ignoring the rule of law. Institutions, constitutions and the rule of law that, however fallible, protect the people against the exercise of arbitrary power.

Talk today, commonplace, of ‘the system’, and how ‘it’s the fault of the system’, buys into the revolutionary mindset that Burke rejected. You see it, also, today, in constant new initiatives, that simply cause change fatigue. Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France was the first work to describe and analyse this phenomenon, and he turned back to the wisdom of the past, and a living and reforming tradition, to reject ‘neophilia’.

So: the power of love, rather than the love of power. An imagination for the whole, rather than the individual part. A respect for traditional ways and the past, rather than revolutionary neophilia.

Fourth, Burke said ‘I love order, for the universe is order.’ Instead of nihilistic chaos, Burke believed that order permeated all aspects of life, from the person living in community and family, to the international sphere. He believed that order was ‘teleological’, which is a word that comes from the Greek for ‘end’ (telos), and means that everything – from the humble worm, to the most complex life has purpose, an end to which it tends. Burke was following Aristotle when he claimed this, and both he and the ancient political philosopher thought the ‘end and purpose of human life was to flourish. For flourishing to be possible, society needed to focus on the ‘common good’ of all, which becomes an end in itself.

Burke thought that order and purpose was divinely ordained: that God was the foundation of truth, beauty and justice, and without belief in God, everything would tend towards chaos, instability and insecurity and the destruction of trust, without which human society falls apart. Today he would profoundly question the widespread assumption of atheism with its closed universe, arguing instead for a porous universe, that is created and sustained in all its beautiful order and pattern by a God of love.

More information about Frances, who has a book coming out soon about Edmund Burke:

The Very Revd Dr Frances E F Ward, Licensed Theologian, the Diocese of Carlisle & Honorary Fellow, St Chad's College, Durham

Published books by Frances Ward